The Cannon River: What’s in a Name, and What’s in the Water?

Living in Northfield with two small boys, questions about the Cannon River are inescapable. “Why is it called the Cannon River?” asks my 6-year-old, probably hoping that the answer has something to do with gunpowder and large projectiles. His brother, not yet attuned to the wonders of artillery, asks “Are there fish in there?” As it turns out, both questions have answers rooted in the rich environmental and economic history of the Cannon River watershed.

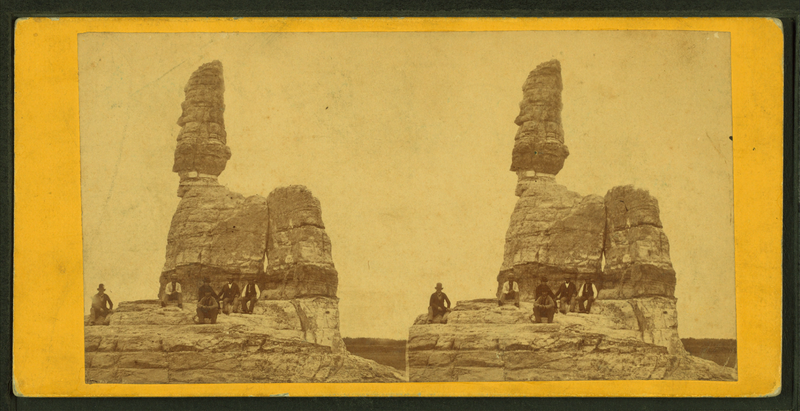

First, the name. What we now call the Cannon River was first known as Inyan Bosndata by the Wahpekute people. The name means “standing rock” in English and refers to the white sandstone formation that also gives Castle Rock its name. The Dakota people used canoes for transportation throughout the watershed, and they often parked them near the river’s mouth, away from the swifter and busier waters of the Mississippi. When French explorers and fur traders arrived in the area, they began to call the river the Riviere aux Canots, or River of Canoes. To many English-speakers, the word “canot” apparently sounded like “cannon,” and by the mid-19th century, the river was being labeled as the Cannon River on maps. My wife, who does not have a degree in French literature, finds this much more understandable than I do. At any rate, “Cannon River” it was, and so it remains.

The short answer to my younger son’s question about fish is, of course, yes. There are fish in there, as the frequent presence of fishermen near Bridge Square attests. By one recent DNR count, there are 47 species in the section of the river near Northfield, including sport fish like walleye, bluegill, pike, bass, and trout. Rice Creek is one of the area’s only naturally reproducing trout streams, and the DNR uses fish from it to stock other waterways. But the health of wildlife in the Cannon wasn’t always a given, and finding a balance between the creatures in the river and the people along it hasn’t always been easy. An anonymous poem as early as 1911 laments the state of the river and complains of rotting vegetation and garbage in the river. In 1958, things were so bad that a DNR memo flatly stated that the river near Faribault was uninhabitable for fish, and it wasn’t all that uncommon to see large numbers of dead and dying fish appear on the river’s surface and banks. Fortunately, that seems to have been the low point for local fish, and though the Cannon still has its problems, commonsense approaches like not dumping raw sewage directly into the river have made a world of difference.

In addition to fish, the river was once home to abundant mussels (in the 20s people remembered the river being “paved” with them), but they were almost completely wiped out by people harvesting mussel shells to make into buttons. It was apparently such a popular endeavor that the Northfield News published a piece in 1904 complaining about the smell from the many mussel corpses littering the riverbank, and by the 1940s mussel sightings had become a rarity. The good news is that mussels seem to be making something of a comeback as well, with more than a dozen species identified in recent surveys.

The Cannon River is full of life, and next time you’re in its neighborhood, take a moment to reflect on the river’s history and all that happens along the banks and in the water of the River of Canoes. If you look hard enough, you may even see a fish in there.